By Syd

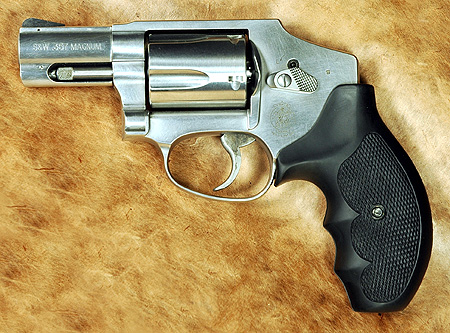

The gun under consideration here is the Smith & Wesson Model 60 J-frame with the 3″ barrel in .357 Magnum, a.k.a., the 60-15. The Model 60 is not a new design. Introduced in 1965, it occupies its own special niche in handgun history. It was the first regular production all-stainless steel revolver, and it was an immediate success. The original Model 60 was a .38 Special. Todays Model 60 is a .357 Magnum. It is available in 2 1/8 barrel, 3 barrel, and 5 barrel versions. Like all J-frames, it chambers 5 rounds. With its longer barrel and grip, it is as if the traditional short barreled snub-nose has been stretched for better performance.

Besides the fact that it was an all-steel J-frame revolver chambered for .357 Magnum, the characteristic which initially appealed to me about this gun was the grip. It felt like it was built for my hand. It’s just a smidgeon longer than the boot grip used on the smaller snubbies and it fills my whole hand. This gun weighs 24 oz. and balances nicely, although it seems just a tad nose heavy. While I like the boot grip on the small snubbies for concealment, it has always been a problem for me in shooting because, like the baby Glocks, I can only get two of three fingers onto the grip and the little finger is left flapping in the breeze. The black rubber Uncle Mikes Combat Grip on the Model 60 fills your hand and gives you much better support for firing hot ammunition. I eventually replaced the Uncle Mike’s Combat Grip with Hogue Monogrips because the Hogue grips are relieved better for speedloaders.

The 3 Model 60 has real sights which are adjustable, the ribbed top rail between the sights, the tapped and screwed-in black rear sight and rail along the top of the frame, and all surfaces are serrated to cut the glare. The front sight leaf is black and is pinned to the barrel. I can actually see these sights. The frame notch sights on the classic snubby really aren’t much use to me, although I have proven that I can use them if I really slow down and get my glaring blurs lined up right. The 3 barrel of the Model 60-15 allows the gun to have a 5 sight radius.

The 3 Model 60 has real sights which are adjustable, the ribbed top rail between the sights, the tapped and screwed-in black rear sight and rail along the top of the frame, and all surfaces are serrated to cut the glare. The front sight leaf is black and is pinned to the barrel. I can actually see these sights. The frame notch sights on the classic snubby really aren’t much use to me, although I have proven that I can use them if I really slow down and get my glaring blurs lined up right. The 3 barrel of the Model 60-15 allows the gun to have a 5 sight radius.

This gun feels more like a 5-shot Model 66 than a lightweight snub-nose. It’s beefy. It has the semi-bull barrel with full length extractor shroud and sights of the S&W magnums. It is, nevertheless, absolutely a J-frame. And it has the slim ergonomic contours which are so appealing about the J-frames. Comparing the Model 60 with a Model 637, everything lines up exactly, down to the smallest contour and detail of the frame: the frame, hammer, trigger, trigger guard, cylinder, and cylinder release are all identical. Where it differs is in the longer grip, longer extractor rod, and the beefier barrel. The longer extractor rod makes it considerably easier to knock the empties clear of the cylinder during a reload.

The 3 barrel and longer grip gives you a gun that performs better than the classic snubby. It has a better sight radius, better muzzle velocity, more reliable spent case ejection, and less punishment to your hands. For these benefits, you lose pocket carry. The 60-15 doesn’t disappear into a pocket like the classic snubby. I would imagine that it would be awkward in a jacket pocket as well.

The 3 barrel and longer grip gives you a gun that performs better than the classic snubby. It has a better sight radius, better muzzle velocity, more reliable spent case ejection, and less punishment to your hands. For these benefits, you lose pocket carry. The 60-15 doesn’t disappear into a pocket like the classic snubby. I would imagine that it would be awkward in a jacket pocket as well.

After a considerable amount of surfing on the web, I have noticed is that it is hard to find holsters for it. Everyone makes leather for 2″ snubbies but very few build them for 3″ versions. Kramer, DeSantis and El Paso all claim to build IWB’s for 3″ j-frames but I’ll bet you they couldn’t do overnight delivery on one. It works with my other snubby holsters that are open on the bottom, like the Galco Speedmaster, Galco Deep Cover, and High Noon Secret Ally. It doesn’t work with the Galco shoulder holster for the snubbies because of the difference in the shape of the grip. Thumb break type holsters which are designed for the snubby boot grip will not work with the Uncle Mikes Combat Grip even though the actual frame of the gun is the same size. The thumb break strap does not reach around the back of the grips. I resolved to order an IWB holster, custom built by Rudy Lozano at Black Hills Leather. It is the subject of a full review found here, but for now I will say that I really like the holster and Rudy.

Aesthetics and Intangibles

Aesthetics and Intangibles

I have been over this revolver with a magnifying glass, and like the other Smith & Wesson wheel guns I have known and loved, it is without flaw in fit or finish. It is good looking but not flashy, compact but very solid, simply good and right and the way it ought to be. Smith & Wesson has produced some weird iron handguns in recent years with exotic metals and day-glo plastic sights, but this isnt one of them. This is a revolver that reflects 149 years of handgun-building experience. Its not an experiment.

The first time I dropped cartridges into the cylinder, generic range ammunition I had never even heard of before, I knew it would fire. I bought some generic range stuff and a couple boxes of premium self defense feed different bullet shapes, charges, even different case lengths in .38 Special, .38 Special +p, and .357 Magnum, and it all fired without a single failure of any kind. I didn’t have to worry about bullet shapes or magazines that the gun didn’t like. There was no break-in period. No doubt, no concern, no need to run 200 rounds through the gun to make sure it worked behold the beauty of the revolver. This is not to say that one should not do reliability testing on a new revolver. On the contrary, one should test a new revolver as rigorously as one tests a new autoloader if the gun’s mission is serious work.

There is something enormously tactile about the Smith & Wesson all-steel revolvers. They feel good and solid in your hand. With an aluminum-frame Airweight, there is always an expectation for it to fall apart in the back of my mind, and with no good reason. My Airweight has literally had thousands of rounds put through it, and some of it has been pretty hot stuff, and it keeps on ticking. It has had much more shooting than these guns are really supposed to have. Dick Metcalfe did a 5000 round torture test on a couple of Airweights using +p feed and neither gun suffered any damage or distortion of the frame. But I still have this thing about the aluminum frame that one day I’m going to over stress it. With the steel guns like the Model 60, you get the feeling that they will still be sending rounds downrange 200 years from now, and probably won’t need service.

Systems which have stood the test of time appeal to me. Smith & Wesson has been building double action revolvers since 1880 a hundred and twenty years. The .38 Special cartridge has been around for a tad better than a hundred years. In that long sweep of time, Smith & Wesson’s double action .38 revolvers have served cops, soldiers, and citizens with distinction and an almost monotonous reliability and effectiveness.

These guns still evoke the cowboy times. The cowboys carried six-shooters but often left the sixth chamber empty so they could put the hammer down without the fear of accidentally setting off a round. So why not build a five-round cylinder with a safe ignition system which would allow the gun to be slim and easier to conceal and carry? Its .357 Magnum chambering reflects the advances in ballistics of the 1930’s. The Model 60, being the first stainless steel revolver, carries the metallurgical advances of the last half of the Twentieth Century. With its key-operated safety lock, it carries the mark of the gun control battles of the late 90’s. Lots of history in these little guns.

These guns still evoke the cowboy times. The cowboys carried six-shooters but often left the sixth chamber empty so they could put the hammer down without the fear of accidentally setting off a round. So why not build a five-round cylinder with a safe ignition system which would allow the gun to be slim and easier to conceal and carry? Its .357 Magnum chambering reflects the advances in ballistics of the 1930’s. The Model 60, being the first stainless steel revolver, carries the metallurgical advances of the last half of the Twentieth Century. With its key-operated safety lock, it carries the mark of the gun control battles of the late 90’s. Lots of history in these little guns.

History won’t save your life in a fight if it is history alone and nothing is learned. The Model 60-15 imparts a feeling that much has been learned, and when you have it in your hand, there is a sense of quiet confidence and competence. In particular, these revolvers are built much stronger than the early models so that they can digest a steady diet of hot ammunition for better hollowpoint performance. The design has been through the fire time and again, and come through. Other handguns will load more rounds, reload faster, and launch powerful rounds, but you know what the Model 60 will do. If you do your part, it will do its part, every time, time after time.

The short-barreled revolvers have one purpose and that is self-defense. They’re not hunting guns, target shooters, or assault weapons. They are completely dedicated. If you’re going to hunt grizzly bears, assault fortified positions, or kick down doors and arrest criminals, the J-Frame revolver is not the gun you would pick for a primary. If you want a highly compact, easily concealed yet powerful personal defense handgun, these revolvers are hard to beat. They are simple, fast, and effective. They remain one of the easiest of all handgun designs to conceal and carry.

Interesting Lawyer-Friendly Stuff

Interesting Lawyer-Friendly Stuff

The Model 60-15 has the integral locking mechanism with the little key-deal that fits in above the cylinder release. I guess this could be handy if my kids were still small. I know that many folks are offended by the imposition of these kinds of reasonable safety measures. They are seen as coerced concessions to states like California and Maryland who are increasingly demanding safety features be added to handguns. I resent being forced to do anything, especially by states that would really like to prohibit firearms altogether. On the other hand, I had small children at home once upon a time, and when they were still little doodles whose judgment I couldn’t completely trust, I used trigger locks on my pistols long before they were fashionable in some circles or mandated. I carried the key on my key ring so it would always be close by. The integral lock on the Model 60 could be useful in a number of situations, such as times when you might have to take the gun off and leave it in a locker or athletic bag.

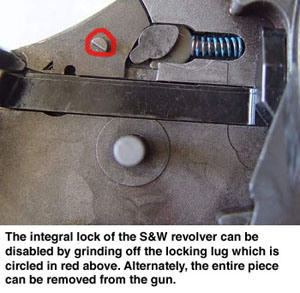

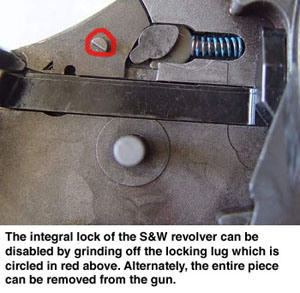

There has been some discussion of these safety locks engaging when they shouldn’t. In the January 2005 issue of American Handgunner, Massad Ayoob published an article about three instances he knew of in which the internal locking device had failed and two of the failures caused the gun to lock up. All three cases were instances in which extremely hot ammunition, such as +p+ and .44 Magnum, were fired from ultra-light scandium and titanium revolvers. Ayoob’s analysis was, This is not necessarily an indictment of Smith & Wesson, nor even of the integral lock system that company uses. It may be more of a lesson that extraordinarily light handguns firing extremely powerful ammunition can be damaged by the battering of constant, extreme recoil forces. Still, it gives us pause. I have not been able to locate any anecdotes so far of the lock engaging during firing on a Model 60. Nevertheless, if this really worries you, it is relatively easy to disable the integral lock.

There has been some discussion of these safety locks engaging when they shouldn’t. In the January 2005 issue of American Handgunner, Massad Ayoob published an article about three instances he knew of in which the internal locking device had failed and two of the failures caused the gun to lock up. All three cases were instances in which extremely hot ammunition, such as +p+ and .44 Magnum, were fired from ultra-light scandium and titanium revolvers. Ayoob’s analysis was, This is not necessarily an indictment of Smith & Wesson, nor even of the integral lock system that company uses. It may be more of a lesson that extraordinarily light handguns firing extremely powerful ammunition can be damaged by the battering of constant, extreme recoil forces. Still, it gives us pause. I have not been able to locate any anecdotes so far of the lock engaging during firing on a Model 60. Nevertheless, if this really worries you, it is relatively easy to disable the integral lock.

It also comes with a little sealed brown paper envelope which contains a single fired case. On the envelope is Smith’s FFL number, make, model, serial number, rifling characteristics, the tester’s name, signature, and date of test. Too bad this one won’t make it into New York’s database.

Range Report

Range Report

The accuracy, weight, ammo versatility, good grip and good sights make this gun a sweet shooter. One of the charming characteristics of revolvers is their tremendous versatility of ammo. Your choices range from powder-puff .38 Special wadcutter all the way up to .357 Magnum. The longer sight radius and better sight picture had me immediately producing far better patterns than I do with traditional styled snub-noses. The additional weight makes it easy on the hands with excellent recoil recovery.

I can make 25-yard shots with a snubby with a hit average of about 3 out of 5 on a small Pepper popper, but if I have to make a 50-yard shot, I would prefer the 1911 or a Hi-Power. I could make a 50-yard shot with the Model 60 if I took my time and handled my trigger right. While I get much better hits with this gun than I do with a snubby, I am nowhere close to the kind of “ragged hole” patterns that I have achieved at times with the 1911. But this just gives me another excuse to go to the range.

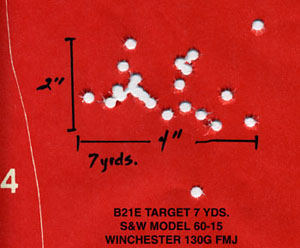

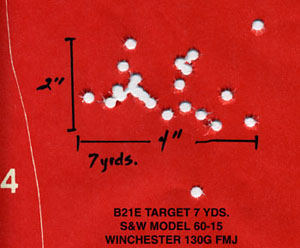

I took the Model 60 to the indoor range and bought a box of Independence .38 Special 130g FMJ, Independence .357 Magnum 158g JSP, Remington Golden Saber +p .38 Special 125g, and a box of Federal .357 Magnum Premium HydraShok, 158g.

I was really pleased with the way the Model 60 shot. The most interesting revelation was that I shot it infinitely better double action than I did single action (still trying to figure out that one). Single action, I was really pitiful, all over the target; double action I started shooting nice grapefruit size patterns at 7 yards, rapid fire, without trying too hard. The tightest 5-shot string was with the Independence .357 a tidy little horizontal string about four inches wide.

The .38 Special was smooth and cream-puffy, nice, and pleasant to shoot. The +p was crisp and authoritative, and I came away with the thought that the +p Golden Saber was the best all-around load, and is the stuff that should be in the speed loaders. The .357 is predictably brisk. After 15 rounds, I was getting some sting in my palm, but I wouldn’t call it “hurt.” It was very manageable, even in rapid fire (“rapid fire” meaning the rate that the beats fall in “Stars and Stripes Forever,” or just as quick as I could regain the sight picture). (And no, Im no Jerry Miculek.)

The worst muzzle flash was from the Golden Saber, followed closely by the Federal, but I didn’t find either blinding.

It was a real delight to buy four boxes of weird-ass ammunition for it and know that all of them were going to work. They did. With a new auto, you really need to run at least 500 rounds through it to make sure it’s reliable and get it broken in. And even with that, you still know in the back of your mind that a bad magazine or an out-of-spec cartridge or poor support can cause it to jam. With several of my 1911’s, I have had to go through a period of working with them to get them to the point where I considered them 100% reliable. The Model 60 doesn’t have any of those issues. It just goes “Bang” every time. (And don’t give me a Glock pitch because they choke up and break parts just like any other gun. I have one shooting buddy who is on his fourth Glock because the previous three have broken.) I traded messages with a Special Forces type who was on his third tour in Afghanistan. His unit had rejected the M9 and adopted one of the Glocks. It broke out in the field and he couldn’t fix it. On his next leave, he bought a Ruger SP101 in .357 said he felt better with it than any of the bottom feeders. Of course, it was a secondary for him, but that spoke chapters and verses to me.

Carry?

Would you use this gun as a carry piece? As a police officer or soldier, no, unless it was a secondary to something with considerably more firepower. As a civilian who tends to mind his own business and not get into shootouts with armed gangs, sure. If you happen to be one of those folks who just prefer revolvers to autos for personal defense, you couldn’t do much better than this. Its not too terribly heavy, but its heavy enough that you can get in some good practice with it without tearing up your hands. If you have a bit of arthritis in your hands or arms and just cant stand the pounding of .45s and .40s, you can load this gun with standard .38 Special and have a soft shooting, but effective personal defense handgun. The extra barrel length will provide for somewhat better muzzle velocity and hollowpoint performance than a 2 snub-nose, usually 50-100 feet per second faster, depending on the load. The muzzle flip and recoil dynamics are not near as violent as with a 2 snub-nose, especially if you like to use +p or .357 loads. I really like to carry the Airweight snubbies but I hate practicing with them because they’re hard on my hands, and yet we know that we must practice with the guns we carry. The Model 60 can provide a vehicle to practice for snubby carry same reload, same ammo, same trigger, same leather without all of the abuse to hands and joints. And also, if you want to carry .357 Magnum in a compact package, the Model 60 in this configuration will handle it without inflicting pain.

With a 5-shot J-frame, the issue of firepower always comes up, and if you want to carry these guns, you have to deal with it. When the balloon goes up, five rounds is not a lot. Five rounds placed well will probably address most of the issues that a civilian will face, but you cant count on that. This means that you have to master the reload with a speed loader. I really like the Safariland Comp I speed loaders. They are spring loaded and kind of shoot the cartridges into the chamber. Another approach is to carry two J-frames, the proverbial New York Reload. When one gun runs dry, you simply draw the other. The New York Reload has some other tactical advantages: if someone manages to get your primary away from you, you have another weapon. Also, you can hand off a second gun to an ally in a situation in which you may be dealing with multiple assailants or have another person with you who you need to protect. Better yet, carry two J-frames and speed loaders. Better to have them and not need them than to need them and not have them. In this era of autoloaders, is it possible that there are tactical advantages to revolvers?

With a 5-shot J-frame, the issue of firepower always comes up, and if you want to carry these guns, you have to deal with it. When the balloon goes up, five rounds is not a lot. Five rounds placed well will probably address most of the issues that a civilian will face, but you cant count on that. This means that you have to master the reload with a speed loader. I really like the Safariland Comp I speed loaders. They are spring loaded and kind of shoot the cartridges into the chamber. Another approach is to carry two J-frames, the proverbial New York Reload. When one gun runs dry, you simply draw the other. The New York Reload has some other tactical advantages: if someone manages to get your primary away from you, you have another weapon. Also, you can hand off a second gun to an ally in a situation in which you may be dealing with multiple assailants or have another person with you who you need to protect. Better yet, carry two J-frames and speed loaders. Better to have them and not need them than to need them and not have them. In this era of autoloaders, is it possible that there are tactical advantages to revolvers?

Training With the Model 60

I took the Model 60, two speedloader pouches, and all seven of my speedloaders to Jim Higginbotham’s match and actually shot the first half of the session with the 5-banger. I only quit when I ran out of ammo and switched to the Commander for the remaining exercises. I got there early so I could talk to him. I opened the conversation with, “I’m going to annoy you today.” “Oh, really? How?” “I’m going to shoot my revolver.” He pulled back the left side of his vest to reveal a huge nickel-plated Model 29 .44 Magnum and said, “I’ve probably got more revolvers on me today than autos.” Another shooter was packing an Airweight as his BUG as well. I felt a little better.

The stages were more revolver friendly than I expected. Most were 3-5 round exercises, sometimes with reloads planned into them, but I didn’t actually have to reload at any time that others didn’t have to. My reloads were, of course, still criminally slow, but getting better. I would do a reload after every string just to practice it and get it smoother. By the end of 50 rounds, I was getting quicker. We did mostly variations on Mozambique and El Presidente with movement and reloads interspersed. I was very pleased with my hits. I only had to endure one, “Those of you who are deploying antique weapons systems are probably running low on ammo now,” after a 5-round stage.

Reloads are a major tactical issue regardless of what gun you use, but they are especially important with revolvers. While five rounds are usually enough for civilian self-defense situations, you have to plan for the instance where it wont be. This means working out a way to carry a reload, and learning to perform the reload in an emergency. Generally, this means using speedloaders. There are currently two speedloaders available for J-frame revolvers, the Safariland Comp 1 and the HKS 36A. Both of these speedloaders have features that commend them. The Safariland Comp 1 has a spring mechanism that releases and launches the cartridges into the cylinder when you push it against the ejector star. The HKS offering has a large knob which must be turned slightly to the right to release the cartridges which fall by gravity into the cylinder. I think the Comp 1 has the edge in speed of reloading, but the HKS is easier to grasp quickly on release knob.

On balances, I came away feeling much better about the wheel gun as a self defense option. The next step is to determine if the skill enhancements with the Model 60 transfer to the Airweight. In terms of reloads, I think it will, but I’m not so sure about marksmanship. The 60 is a whole lot easier to get good hits with than its short barreled cousins.

Summary

The Model 60-15 is a versatile and accurate revolver. It is somewhat larger and heavier than the classic snubby, but its size and weight enable it to be a pleasant practice gun without being too large for discrete concealed carry. Its longer barrel produces better performance in .38 Special ammunition, and its greater weight allows it handle full charge .357 Magnum without causing pain. The Model 60-15 is a solid performer which is a pleasure to shoot. For wheel gun fans, this is one that I would heartily recommend.

Smith & Wesson Models 40, 42, 640, 940, 442, 642, 340Sc, 342Ti and 340PD

Smith & Wesson Models 40, 42, 640, 940, 442, 642, 340Sc, 342Ti and 340PD

By Syd

By Syd

Following my stunning success with changing out the spring set in the Model 60, I decided that I’d take on the Airweight. Should be all the same, right? Wrong. I took it all apart, cleaned out eight years worth of crud, polished and lubed. I installed the same springs I used in the Model 60 the 8 lb. hammer spring and the 14 lb. rebound spring. No matter what I did, the rebound slide wouldn’t work right with the Wolff spring in it. It would buck up in the front instead of moving straight back when the trigger was pulled. I took the thing in and out so many times that my thumb got raw from putting the rebound spring back in. Then to make matters worse, I pulled the cylinder hand off of the trigger, not realizing that there was a little spring hidden in the body of the trigger. Of course, when I put it back together, it didn’t work right. Research project. Oh, there’s a little spring somewhere. Miracle of miracles, I managed to find the spring among the dust bunnies and I had no idea of how it went back in. Spent some time searching the Smith & Wesson forum and found some instructions for how to get the little child of Satan back in. (Its also in the Kuhnhausen manual, but I didnt know that at the time.) Getting the spring back in wasn’t too terribly hard. The rebound slide bucking was another thing, however. Nothing I did would make it work. I finally put the stock rebound spring back in and everything was Jake.

Following my stunning success with changing out the spring set in the Model 60, I decided that I’d take on the Airweight. Should be all the same, right? Wrong. I took it all apart, cleaned out eight years worth of crud, polished and lubed. I installed the same springs I used in the Model 60 the 8 lb. hammer spring and the 14 lb. rebound spring. No matter what I did, the rebound slide wouldn’t work right with the Wolff spring in it. It would buck up in the front instead of moving straight back when the trigger was pulled. I took the thing in and out so many times that my thumb got raw from putting the rebound spring back in. Then to make matters worse, I pulled the cylinder hand off of the trigger, not realizing that there was a little spring hidden in the body of the trigger. Of course, when I put it back together, it didn’t work right. Research project. Oh, there’s a little spring somewhere. Miracle of miracles, I managed to find the spring among the dust bunnies and I had no idea of how it went back in. Spent some time searching the Smith & Wesson forum and found some instructions for how to get the little child of Satan back in. (Its also in the Kuhnhausen manual, but I didnt know that at the time.) Getting the spring back in wasn’t too terribly hard. The rebound slide bucking was another thing, however. Nothing I did would make it work. I finally put the stock rebound spring back in and everything was Jake.

By Ronald S. Markowitz

By Ronald S. Markowitz

The 3 Model 60 has real sights which are adjustable, the ribbed top rail between the sights, the tapped and screwed-in black rear sight and rail along the top of the frame, and all surfaces are serrated to cut the glare. The front sight leaf is black and is pinned to the barrel. I can actually see these sights. The frame notch sights on the classic snubby really aren’t much use to me, although I have proven that I can use them if I really slow down and get my glaring blurs lined up right. The 3 barrel of the Model 60-15 allows the gun to have a 5 sight radius.

The 3 Model 60 has real sights which are adjustable, the ribbed top rail between the sights, the tapped and screwed-in black rear sight and rail along the top of the frame, and all surfaces are serrated to cut the glare. The front sight leaf is black and is pinned to the barrel. I can actually see these sights. The frame notch sights on the classic snubby really aren’t much use to me, although I have proven that I can use them if I really slow down and get my glaring blurs lined up right. The 3 barrel of the Model 60-15 allows the gun to have a 5 sight radius. The 3 barrel and longer grip gives you a gun that performs better than the classic snubby. It has a better sight radius, better muzzle velocity, more reliable spent case ejection, and less punishment to your hands. For these benefits, you lose pocket carry. The 60-15 doesn’t disappear into a pocket like the classic snubby. I would imagine that it would be awkward in a jacket pocket as well.

The 3 barrel and longer grip gives you a gun that performs better than the classic snubby. It has a better sight radius, better muzzle velocity, more reliable spent case ejection, and less punishment to your hands. For these benefits, you lose pocket carry. The 60-15 doesn’t disappear into a pocket like the classic snubby. I would imagine that it would be awkward in a jacket pocket as well. Aesthetics and Intangibles

Aesthetics and Intangibles These guns still evoke the cowboy times. The cowboys carried six-shooters but often left the sixth chamber empty so they could put the hammer down without the fear of accidentally setting off a round. So why not build a five-round cylinder with a safe ignition system which would allow the gun to be slim and easier to conceal and carry? Its .357 Magnum chambering reflects the advances in ballistics of the 1930’s. The Model 60, being the first stainless steel revolver, carries the metallurgical advances of the last half of the Twentieth Century. With its key-operated safety lock, it carries the mark of the gun control battles of the late 90’s. Lots of history in these little guns.

These guns still evoke the cowboy times. The cowboys carried six-shooters but often left the sixth chamber empty so they could put the hammer down without the fear of accidentally setting off a round. So why not build a five-round cylinder with a safe ignition system which would allow the gun to be slim and easier to conceal and carry? Its .357 Magnum chambering reflects the advances in ballistics of the 1930’s. The Model 60, being the first stainless steel revolver, carries the metallurgical advances of the last half of the Twentieth Century. With its key-operated safety lock, it carries the mark of the gun control battles of the late 90’s. Lots of history in these little guns. Interesting Lawyer-Friendly Stuff

Interesting Lawyer-Friendly Stuff There has been some discussion of these safety locks engaging when they shouldn’t. In the January 2005 issue of American Handgunner, Massad Ayoob published an article about

There has been some discussion of these safety locks engaging when they shouldn’t. In the January 2005 issue of American Handgunner, Massad Ayoob published an article about  Range Report

Range Report With a 5-shot J-frame, the issue of firepower always comes up, and if you want to carry these guns,

With a 5-shot J-frame, the issue of firepower always comes up, and if you want to carry these guns,

I’ll admit to a preference for exposed hammer revolvers. I don’t know why really. Maybe its the traditionalist in me. Maybe it’s because I like to have the option to fire single action if I want to. Single action fire is generally thought to be more accurate than double action. When target shooting and hunting, people prefer to manually cock the hammer to get that wonderful crisp 1 lb. trigger that a good revolver firing single action can give you. The sights just move around less when you don’t have to apply the force needed to cock the hammer.

I’ll admit to a preference for exposed hammer revolvers. I don’t know why really. Maybe its the traditionalist in me. Maybe it’s because I like to have the option to fire single action if I want to. Single action fire is generally thought to be more accurate than double action. When target shooting and hunting, people prefer to manually cock the hammer to get that wonderful crisp 1 lb. trigger that a good revolver firing single action can give you. The sights just move around less when you don’t have to apply the force needed to cock the hammer. A friend of mine and I have an ongoing debate about which snubby is uglier, the Centennial or the Bodyguard. The camel hump hammer shroud on the back of the Bodyguard’s frame, while eminently sensible, has never appealed to my eye. However, it is completely functional. The hammer shrouded Bodyguard, unlike the Centennial, remains snag-free for pocket carry while allowing for single-action fire. The hump also helps the Bodyguard to stay in position when carried in a pocket holster.

A friend of mine and I have an ongoing debate about which snubby is uglier, the Centennial or the Bodyguard. The camel hump hammer shroud on the back of the Bodyguard’s frame, while eminently sensible, has never appealed to my eye. However, it is completely functional. The hammer shrouded Bodyguard, unlike the Centennial, remains snag-free for pocket carry while allowing for single-action fire. The hump also helps the Bodyguard to stay in position when carried in a pocket holster. In 1985, the Model 649 was introduced. It was a stainless steel version of the Model 49, and it was built until 1996. In 1997 the Model 49 was discontinued in favor of the stainless Model 649 in .357 Magnum.

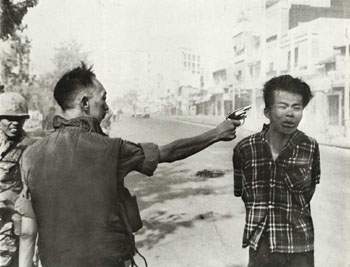

In 1985, the Model 649 was introduced. It was a stainless steel version of the Model 49, and it was built until 1996. In 1997 the Model 49 was discontinued in favor of the stainless Model 649 in .357 Magnum. Perhaps the most infamous photograph of a pistol from the Twentieth Century involves the Smith & Wesson Bodyguard. It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1969. It is the picture of South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting a Viet Cong captain named Bay Lop in the head. I hesitate to bring up this incident, but at the same time, it is impossible for me to chart the history of this hand gun without acknowledging this moment in history.

Perhaps the most infamous photograph of a pistol from the Twentieth Century involves the Smith & Wesson Bodyguard. It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1969. It is the picture of South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting a Viet Cong captain named Bay Lop in the head. I hesitate to bring up this incident, but at the same time, it is impossible for me to chart the history of this hand gun without acknowledging this moment in history. By Syd

By Syd In 1942 Smith & Wesson built a few Victory Model Military & Police revolvers with 2″ barrels. In 1946, they began commercial production of the

In 1942 Smith & Wesson built a few Victory Model Military & Police revolvers with 2″ barrels. In 1946, they began commercial production of the  The Rationale of the Snubnose

The Rationale of the Snubnose The Art of Compromise

The Art of Compromise

Conceal-ability

Conceal-ability A Gun That Is Always With You

A Gun That Is Always With You The North American Mini Revolver may be somewhere outside of the realm of guns we usually think of as snubnose revolvers, but it is a short barreled, compact revolver, and it performs many of the same functions we associate with snubnoses: it is very concealable and easy to carry, and it is a dedicated self-defense pistol.

The North American Mini Revolver may be somewhere outside of the realm of guns we usually think of as snubnose revolvers, but it is a short barreled, compact revolver, and it performs many of the same functions we associate with snubnoses: it is very concealable and easy to carry, and it is a dedicated self-defense pistol. Few handguns are the subject of more heated controversy than these tiny revolvers. Some disparage them as simply too small and too inaccurate to serve as legitimate self-defense weapons. Others swear by them as their all the time gun that can go anywhere all the time and remain undetectable where larger guns would be a problem. Much of this comes down to an individuals philosophy about personal defense weapons. It is estimated that in approximately 92% of firearms self-defense situations, no shots are fired; the appearance of the gun is enough to stop the action. If no shots are fired, a .22 is as good as a .45 and a whole lot lighter. If, on the other hand, your world-view includes a high probability of running gun battles with multiple armed assailants, the Mini Revolver would certainly not be the appropriate armament.

Few handguns are the subject of more heated controversy than these tiny revolvers. Some disparage them as simply too small and too inaccurate to serve as legitimate self-defense weapons. Others swear by them as their all the time gun that can go anywhere all the time and remain undetectable where larger guns would be a problem. Much of this comes down to an individuals philosophy about personal defense weapons. It is estimated that in approximately 92% of firearms self-defense situations, no shots are fired; the appearance of the gun is enough to stop the action. If no shots are fired, a .22 is as good as a .45 and a whole lot lighter. If, on the other hand, your world-view includes a high probability of running gun battles with multiple armed assailants, the Mini Revolver would certainly not be the appropriate armament. Tactics

Tactics

Its always entertaining to me to read the noise that gets passed off as gun wisdom on the Internet, and no subject seems to collect more ill-considered pseudo-truths than the snub-nose revolver. With the disclaimer that if I were forced to choose one pistol for my life, it wouldn’t be a snub-nose .38 Special, I want to address some of the issues and criticisms often leveled at the snub-nose. The big one, of course, is that it only holds five rounds, and I admit that this is my biggest negative with the gun. But think about it a minute unless you are a soldier or a guy who kicks down doors for a living, how often have you actually been in a situation (outside of an IDPA match) in which there was a high likelihood of needing to fire 16-30 rounds? I have read the gun news almost every day for years and the instances in which an armed civilian has been called upon to shoot it out with a gang of heavily armed adversaries are exceedingly rare. And further, the sad fact is that if you have to go up against a half dozen armed people your odds of winning aren’t very good even with a gun that holds 15 rounds. Generally, violent crime is a matter of 1, 2 or 3 against 1 according to Justice Department statistics. The overwhelming majority of people who commit violent crimes against strangers are trying to steal something or commit a sexual assault. These people are looking for a score, not a gunfight. A .38 Special revolver with five or six rounds is quite adequate to dissuade, or if need be, stop this kind of predator, assuming of course that you can put the rounds somewhere that they will incapacitate the attacker. Also, with practice, a revolver can be reloaded as fast, or nearly so, as an auto using speed loaders.

Its always entertaining to me to read the noise that gets passed off as gun wisdom on the Internet, and no subject seems to collect more ill-considered pseudo-truths than the snub-nose revolver. With the disclaimer that if I were forced to choose one pistol for my life, it wouldn’t be a snub-nose .38 Special, I want to address some of the issues and criticisms often leveled at the snub-nose. The big one, of course, is that it only holds five rounds, and I admit that this is my biggest negative with the gun. But think about it a minute unless you are a soldier or a guy who kicks down doors for a living, how often have you actually been in a situation (outside of an IDPA match) in which there was a high likelihood of needing to fire 16-30 rounds? I have read the gun news almost every day for years and the instances in which an armed civilian has been called upon to shoot it out with a gang of heavily armed adversaries are exceedingly rare. And further, the sad fact is that if you have to go up against a half dozen armed people your odds of winning aren’t very good even with a gun that holds 15 rounds. Generally, violent crime is a matter of 1, 2 or 3 against 1 according to Justice Department statistics. The overwhelming majority of people who commit violent crimes against strangers are trying to steal something or commit a sexual assault. These people are looking for a score, not a gunfight. A .38 Special revolver with five or six rounds is quite adequate to dissuade, or if need be, stop this kind of predator, assuming of course that you can put the rounds somewhere that they will incapacitate the attacker. Also, with practice, a revolver can be reloaded as fast, or nearly so, as an auto using speed loaders. One pseudo-truth I hear a lot is that snub-nose J-frames are the best choice for women, beginners and people who don’t want to practice with their handguns. Why? Loading and firing a Kahr or Glock is not exactly rocket science. A 1911 is only slightly more complicated. Are women and newbies too stupid to learn to operate an autoloader? How do they manage to operate their cars and food processors? I would argue the other way: let the newbies get a nice medium size autoloader with a deep magazine and a full size grip so they can miss a lot and not destroy their hands learning to fire the gun. A larger revolver is also a good choice for a newbie. A snub-nose 5-banger actually requires more skill to use effectively. With only five rounds in the gun, there is a smaller margin for error you cant afford to miss. The heavy trigger and short sight radius require more skill rather than less to achieve accuracy. You have to practice with these guns. Actually, you have to practice with any handgun, but that’s another rant. Especially with the lightweight revolvers, practice can be unpleasant because of the brisk recoil and muzzle flip, so why saddle newbies with little pocket cannons that are going to discourage practice? The only rational reason to put a newbie into a revolver is that they like it better. There is a certain wonderful trustworthiness about a wheel gun. Autos are mysterious with a lot of strange parts and such. Revolvers are simple and obvious. If the newbie has confidence that the revolver is going to work for them when the chips are down, that’s the gun they should get. Then they should buy a case of ammo (and maybe some shooting gloves) and learn how to use it.

One pseudo-truth I hear a lot is that snub-nose J-frames are the best choice for women, beginners and people who don’t want to practice with their handguns. Why? Loading and firing a Kahr or Glock is not exactly rocket science. A 1911 is only slightly more complicated. Are women and newbies too stupid to learn to operate an autoloader? How do they manage to operate their cars and food processors? I would argue the other way: let the newbies get a nice medium size autoloader with a deep magazine and a full size grip so they can miss a lot and not destroy their hands learning to fire the gun. A larger revolver is also a good choice for a newbie. A snub-nose 5-banger actually requires more skill to use effectively. With only five rounds in the gun, there is a smaller margin for error you cant afford to miss. The heavy trigger and short sight radius require more skill rather than less to achieve accuracy. You have to practice with these guns. Actually, you have to practice with any handgun, but that’s another rant. Especially with the lightweight revolvers, practice can be unpleasant because of the brisk recoil and muzzle flip, so why saddle newbies with little pocket cannons that are going to discourage practice? The only rational reason to put a newbie into a revolver is that they like it better. There is a certain wonderful trustworthiness about a wheel gun. Autos are mysterious with a lot of strange parts and such. Revolvers are simple and obvious. If the newbie has confidence that the revolver is going to work for them when the chips are down, that’s the gun they should get. Then they should buy a case of ammo (and maybe some shooting gloves) and learn how to use it. The Good Stuff

The Good Stuff